Scientists Review New Research Strategies for Treating CLL

Approaches such as new types of monoclonal antibodies and chimeric antigen receptor natural killer cells could change how chronic lymphocytic leukemia is treated, according to a recent review article.

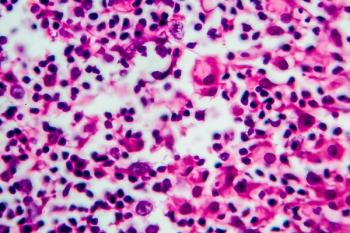

New advances in scientists’ understanding of how immune and tumor cells interact is paving the way for promising new immunotherapies against

Corresponding author Marta Coscia, MD, PhD, of the University of Torino, in Italy, and colleagues explained that to date, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies have been the main immunotherapy leveraged against CLL. Other approaches at immunotherapy have been less successful, they noted.

“Unfortunately, despite initial promising data, results from pilot clinical studies have not shown optimal results in terms of disease control—especially when immunotherapy was used individually—largely due to CLL-related immune dysfunctions hampering the achievement of effective anti-tumor responses,” they wrote.

The investigators outlined 3 types of antibody-based therapies. The first monoclonal antibody therapy for CLL targeted CD20, which is expressed on the surface of B cells. Newer efforts are underway, however, to target CD19, CD37, and B-cell activating factor, among others.

Other types of antibodies have also been developed, such as bi-specific antibodies, which are “molecules that combine antibody directed therapies with cellular mediated immunotherapy.” Blinatumomab (Blincyto) was the first bi-specific antibody tested in CLL, the investigators said. It is a bi-specific T-cell engager, targeting CD19 and CD3.

“Preclinical studies revealed that blinatumomab possesses a potent anti-tumor activity, being able to effectively eliminate CLL cells in a mouse-xenograft model and in samples from both treatment-naïve and previously treated CLL patients,” they wrote.

However, there is not yet data on safety or efficacy in human patients.

Another type of bispecific antibody, MGD011, targets CD3 and CD19. In contrast to blinatumomab, MGD011 is a dual affinity retargeting antibody. The therapy was shown to be effective in vitro at killing CLL cells by leveraging CLL-derived T cells.

“These preclinical results indicated that MGD011 was capable [of partially restoring] immunological dysfunctions of T cells from CLL patients, resulting in the induction of their activation and proliferation markers,” they explained.

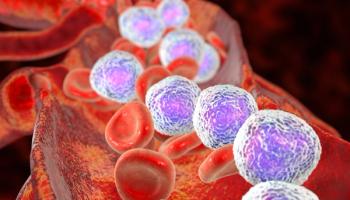

A third type of monoclonal antibodies is bi- or tri-specific killer engagers. These “BiKE” or “TriKes” recruit natural killer (NK) cells to target tumor antigens, Coscia and colleagues said. Preliminary findings suggest this type of therapy could be a “compelling” weapon against CLL, the authors said, and warrant further investigation.

Turning their attention to adoptive-cell therapies, the investigators said chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have been the most studied therapies in B-cell hematological malignancies, offering both the benefits of T cells and antibodies. Yet, the investigators said their use is controversial in CLL.

“The main limitation of a successful use of CAR T cells in CLL is the occurrence of intrinsic dysfunctions of the T-cell compartment that can interfere with the expansion and functionality of engineered T cells,” they wrote.

Coscia and colleagues said work is underway on a number of different strategies designed to overcome the challenges of CAR T-cells in this patient group.

At the same time, they said adoptive-cell research is also taking place into NK cells. Early research into CAR NK cells suggests the therapy is safe in patients with relapsed or refractory CLL, without some of the drawbacks seen in CAR T cells.

“Most importantly, results from this study suggest that CAR NK cell-therapy do not produce any major CAR T-cell treatment-related toxic effects, such as cytokine release syndrome or neurotoxicity, and, as expected, there was no evidence of [graft-versus-host disease],” they wrote.

The authors concluded by discussing the potential of combination therapies, such as anti-PD1 immune checkpoint inhibitors and the tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica), which is currently the subject of clinical trials.

Reference

Perutelli F, Jones R, Griggio V, Vitale C, Coscia M. Immunotherapeutic strategies in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: advances and challenges. Front Oncol. Published online February 21, 2022. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.837531

Newsletter

Stay ahead of policy, cost, and value—subscribe to AJMC for expert insights at the intersection of clinical care and health economics.