Dual US, China Approval Process for Zanubrutinib Shows Regulatory Differences

The process of approving a new therapy for relapsing and/or remitting mantle cell lymphoma therapy got off to a faster start in China, but United States regulators caught up and approved the drug first.

The recent approval of the second-generation Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor zanubrutinib (Brukinsa) is elucidating synergies and discrepancies between the regulatory approval processes of the United States and China.

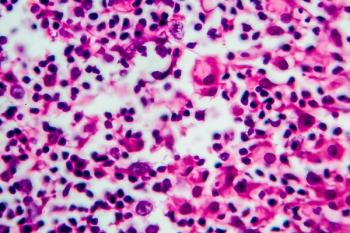

The drug, which was approved to treat relapsed and/or refractory

Zanubrutinib was first discovered in 2012, and a study of patients with B cell malignancies began in Australia in 2014. It later included US patients. Those data led the drug’s developer to begin discussions with the Chinese New Medical Products Administration (NMPA) about a possible approval for patients with R/R MCL based on a single-arm phase 2 trial. The company eventually filed a New Drug Administration (NDA) with the Chinese regulator in August 2018. They were granted conditional approval on June 3, 2020.

At the same time, the agency was working with the FDA. Their trial data led to a pre-NDA meeting with the FDA in August 2018, but the regulator asked for longer follow-up monitoring before the NDA was filed. The filing eventually came in June 2019 and the FDA granted accelerated approval to the drug in November 2019.

Chen and colleagues wrote that the drug’s 59% complete response rate among patients with R/R MCL in the phase 2 trial was compelling, and the drug had solid tolerability and safety profiles.

One issue during the approval process was the population used in the study. Chen and colleagues said this was the first time they had heard of an FDA approval based on pivotal data from a primarily Chinese population, which meant the demographic data underpinning the study was significantly different than most NDAs the FDA reviews.

“On average, only 22% of patients included in previous pivotal trials of anticancer drugs approved by the FDA were of Asian ethnicity,” they wrote. They said the FDA considered population representativeness, ethnic differences, and safety data when evaluating the NDA.

Though both the NMPA and FDA would eventually approve the drug, the approvals came months apart, and the agency that initially moved fastest, the NMPA, ended up issuing an approval nearly 7 months after the FDA.

The authors noted that both the FDA and NMPA have similar procedures, including pre-NDA meetings, NDA acceptance, filing review, technical review and on-site inspections.

“Nevertheless, discrepancies in the review cycles and sequence of procedures widened the time gap between the two approvals,” Chen and colleagues wrote. For instance, they noted that the FDA had stricter requirements to accept an NDA, but then attempted to complete their review in a single cycle. The NMPA, on the other hand, generally asks for one or more rounds of supplemental data following an NDA.

The Chinese agency also conducted a full-scale inspection of the new manufacturing facility built to make the drug, but the FDA opted for spot-checks based on the manufacturer’s solid record of compliance.

Chen and colleagues said China has made significant progress improving its drug approval process, but they said there is more work to be done.

Reference

Li G, Liu X, Chen X. Simultaneous development of zanubrutinib in the USA and China. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(10):589-590. doi:10.1038/s41571-020-0414-y

Newsletter

Stay ahead of policy, cost, and value—subscribe to AJMC for expert insights at the intersection of clinical care and health economics.